Everything starts with a sketch. How meticulously that sketch is subsequently brought to life, however, remains to be seen. Imagine that you design something – a cathedral, in this case – and then it takes another six hundred years before the building is actually ‘finished’. 'Finished', because even after six centuries, not all details seem to have been perfected. Is it still your design?

Everything starts with a sketch

The 78 architects of the Duomo de Milano

Freed from the tyrant

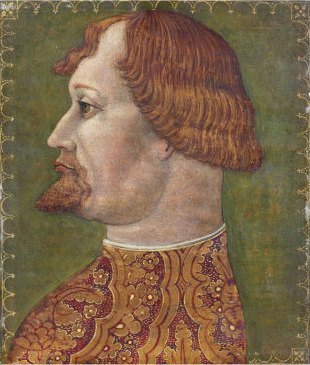

In 1386, a procession headed by Gian Galeazzo Visconti arrives in Milan. His then reigning uncle, tyrant Bernabò Visconti, thinks he can laugh at his ridiculous nephew with his procession, but not much later finds himself deposed and locked up in a prison.

Pride of the people

The people are freed from the tyrant, but the new count of Milan does not want to stop there. Two weeks later, together with Archbishop Antonio da Saluzzo, he initiates the construction of a gigantic cathedral in the heart of Milan that is supposed to become the pride of the people: the Duomo di Milano.

Lombard architectural style

Four buildings stand on the spot where this new structure is to be built. Three will be demolished, the fourth will be operated as a quarry. The original design for the cathedral was to be executed in a brick construction decorated with a terracotta covering, probably comparable to churches such as the Carmine in Milan.

The first architect: Simone da Orsenigo

This Gothic Lombard style was chosen by the first chief engineer of the Duomo di Milano. From 1387 to 1389, Simone da Orsenigo led more than three hundred employees of the Fabbrica del Duomo, the organization that maintains the complete construction and reconstruction of the cathedral to this day. At his side worked several other architects during this period.

A new vision

The autumn of 1387 marks a turning point: Gian Galeazzo Visconti, who in two years has already conquered almost all of Northern Italy and has married off his daughter Valentina to the brother of the King of France, decides to transform the advertising medium – the Duomo – to a royal symbol.

Visconti has new ideas about the style of the Duomo. He gives the Fabbrica exclusive access to the Candoglia quarry, where all the marble for the cathedral has been extracted from, until today. This is a departure from the original Romanesque design, which was to be executed in brick. Within a few years, Orsenigo's design, the basis for the cathedral, has changed considerably.

Modern style, modern architect

This new architectural style also requires a new mentality and better technical skills. In 1389, Visconti appoints a new chief engineer who further modifies Orsenigo's designs to bring them more in line with what was considered modern European architecture at the time, a style not yet widely accepted in that region. The masonry and the pylons will therefore be built "in caisson": load-bearing outer walls in Candoglia marble filled with stones on the inside.

The fifth architect: Nicolas de Bonaventure

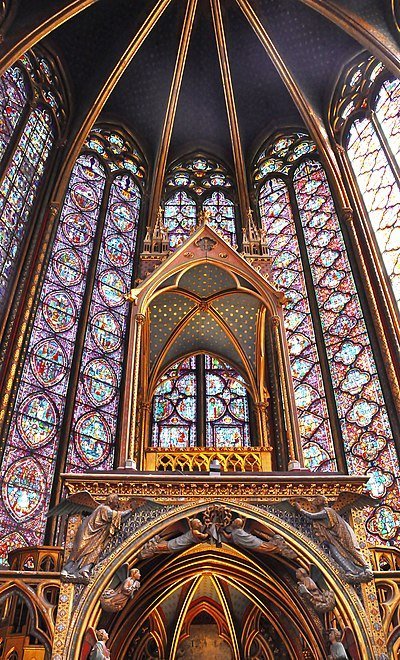

Nicolas de Bonaventure, the fifth architect to work on the Duomo, gives the Lombard Gothic design a Rayonnant Gothic twist. Rayonnant Gothic, often seen as part or succession of the late French Gothic, literally means "radiant" Gothic. Light effect and transparency are central, rose windows are an important point of recognition.

Although Bonaventure only worked on the Duomo for a year, his French stamp on the building is clearly visible. His French taste is reflected in the elegant pylons, plinths and the three large windows of the apse.

Mathematical model

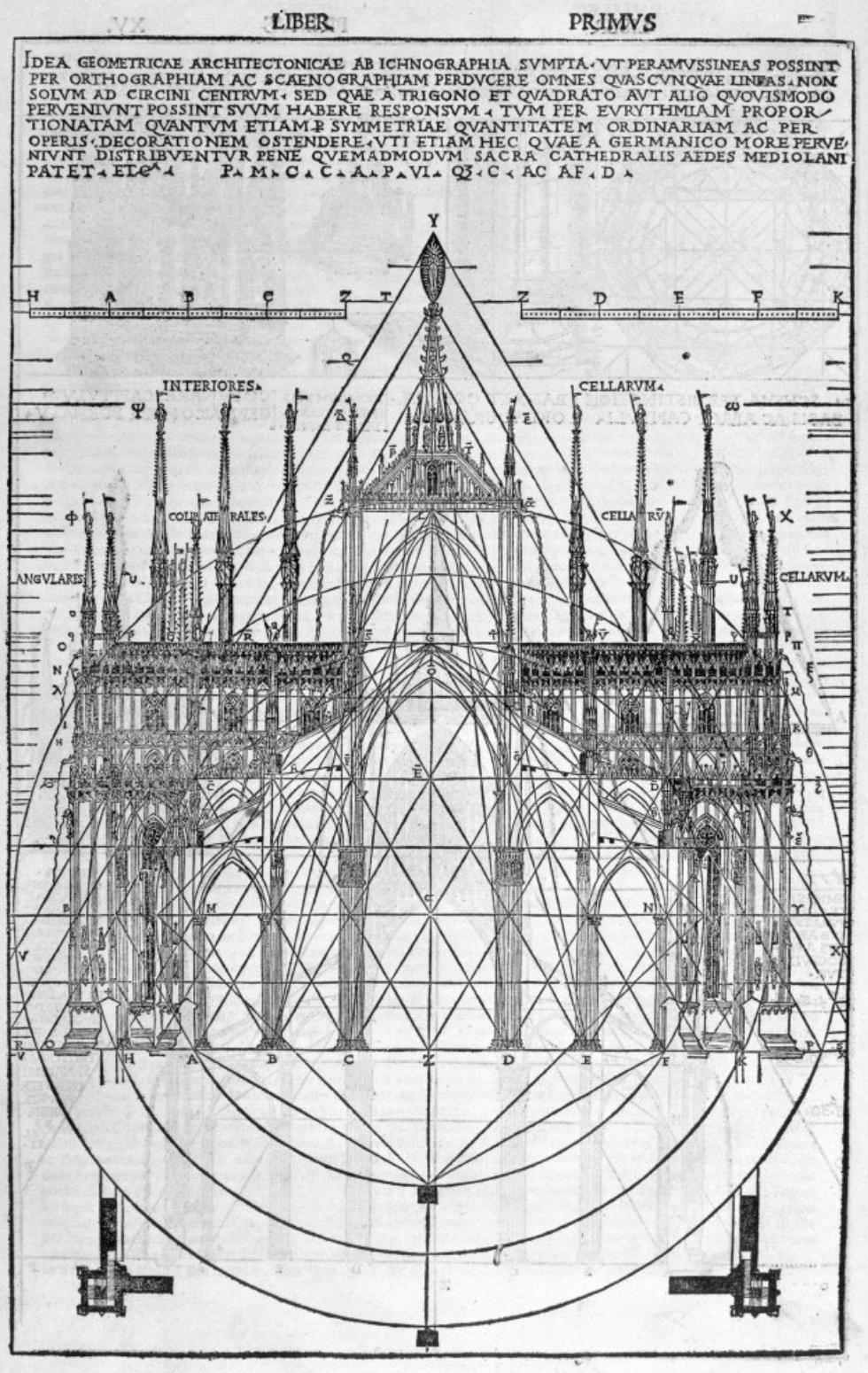

Work is progressing steadily, but in order to finish the pylons and place the capitals, it was still necessary to determine how high they should be. Various architects and mathematicians, including Heinrich Parler and Gabriele Scovaloca, tackled this question in 1391, a year in which at least five other architects worked on the Duomo.

Scovaloca's model remains closest to the Lombard building tradition and becomes the winning model. We see this way of working a lot in the history of the Duomo: for a problem, various scholars from all over Europe are asked to submit a solution, of which the best option is implemented. Scovaloca's design is even cited later in Cesariano's 16th-century Italian translation of Vitruvius' De architectura.

The eighteenth architect: Jean Mignot

At this point, it becomes increasingly difficult to trace which architects worked on the Duomo and when. It is therefore not certain whether Jean Mignot is exactly the eighteenth architect, but in 1399 a French engineer is again called upon to find a solution for the work that has to be carried out at ever greater heights.

Jean Mignot is not pleased with what has been built so far. He calls it a 'pericolo di ruina': according to him, the entire building is about to collapse. Despite the fact that it turns out to be better than expected, the 'disintegration' is, between 1400 and 1401, completely turned upside down, and his progressive vision helps to realize better techniques and working methods.

33 architects and an 80-year break

Until Visconti's death in 1402, the construction of the cathedral progressed rapidly. After this, however, the process comes to a standstill. In the eighty years that followed, only a few parts of the then half-completed cathedral were completed, including two tombs, the windows of the apse, the nave and the aisles up to the sixth bay. At that time, sixty-six years have passed, and thirty-three architects have attempted to provide the cathedral with their vision.

Religious choices

After the appearance of some interesting names, such as Leonardo da Vinci – who eventually withdraws his design for a dome – we jump forward in time. Carlo Borromeo becomes the new archbishop. He has strong religious beliefs and removes the tombs of several predecessors from the cathedral.

The forty-seventh architect: Pellegrino Pellegrini

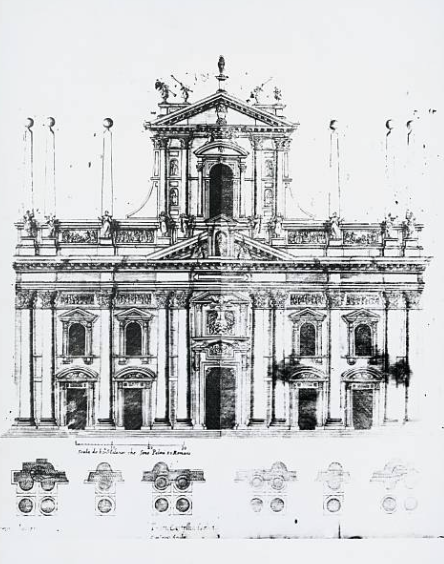

In 1571, Borromeo appoints Pellegrino Pellegrini as chief engineer, who is approximately the forty-seventh architect. Together they strive for a new look of the cathedral that emphasizes the Romano-Italian nature of the building and the people. The Gothic style of the cathedral is still not accepted because it is Protestant in Germanic style, in origin. The Renaissance style is Romanesque, Catholic, and therefore the right direction according to Borromeo and Pellegrini.

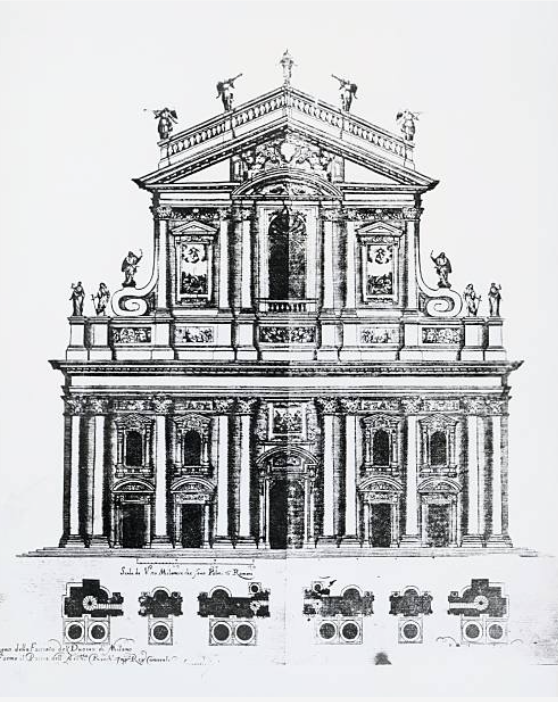

Pellegrini's facade

Because the facade is still unfinished, and is the most visible part of the cathedral, this was to be addressed first. Pellegrini designed a facade in Roman style, in which the Gothic style that was leading for centuries is virtually hidden. It takes until 1615 before an agreement is finally reached and the foundations for yet another new design are laid.

The fifty-second architect: Fabio Mangone

Federico Borromeo continues where his predecessor left off, and under the direction of chief engineers Richini and Fabio Mangone, the fifty-second architect at least, Pellegrini's design is refined and further implemented.

The sixty-first architect: Carlo Buzzi

However, it was not long before the new architect of the Fabbrica, Carlo Buzzi, made a radical decision in 1649: the façade must be returned to its original Gothic style. Large Gothic pillars and bell towers are added to the design and the 90-degree angle of the roof is again accentuated as in Simone da Orsenigo's original design.

The sixty-seventh architect: Francesco Corce

In 1765 the cathedral has hardly any spires. Nevertheless, it is decided to build the main spire, to a dizzying height of 108.5 meters. Architect Francesco Croce realizes the design in Gothic style with the aim of giving the city strength and power. Atop the spire is the Madonnina, a landmark to the Milanese to this day, and a reminder to keep looking up.

Napoleon's order

On May 20, 1805, Napoleon gives the order to finally finish the facade of the cathedral. He will be crowned King of Italy six days later, and in his euphoria, he promises to take on all the costs of finishing the cathedral’s facade. De Fabbrica sells all of its real estate, but never receives payment. Meanwhile, the statue of San Napoleon looks down on the city from one of its towers, intended as an expression of gratitude for the promise of his financial help.

Buzzi's facade

Buzzi's 1649 design for the façade will be realized in the years that follow. Although part of the work is being carried out by Francesco Soave, the approximately sixty-ninth architect, architects Carlo Amati and Giuseppe Zanoja, architects seventy-three and seventy-four, are given credit for finally completing the facade of the Duomo di Milano.

The final stages

In the 19th century, the construction of many towers, pinnacles, spires, statues and arches remained. In 1884, the facade was restored, part of which was the installation of the first of the famous doors, the door of Pogliaghi.

Only when the very last door is inaugurated on January 6, 1965, does the construction of the Duomo di Milano reach its real end. But even now the Fabbrica is not standing still. Restoring and maintaining one of the largest cathedrals in the world is a never-ending process.

From sketch to 'final' result

The final result – 11,700 square meters, 135 towers, 3159 statues, 55 stained glass windows, 96 gargoyles – is one in which many architectural styles are mixed. In addition to the 78 well-known architects and engineers, thousands of others, from workers to consultants, have contributed to this iconic cathedral.

The extent to which Orsenigo's design has been preserved is debatable. In general, the building may correspond to the very first sketch, but few details will be exactly executed. The building is 'finished' for now, but there is a chance that it has not yet met its last architect.